Birds nested using radioactive mud from WW II-era nuclear bomb production plant,

stopping attempts to clean up some of the worst leaking atomic waste,

much of which is liquid in leaking tanks near the Columbia River.

We have nuclear plants leaking radioactive tritium next to the Chattahoochee

and Altamaha Rivers, and radiation is detectible in the Savannah River

near Plant Vogtle.

How many radioactive solar panels or windmills have you heard of?

stopping attempts to clean up some of the worst leaking atomic waste,

much of which is liquid in leaking tanks near the Columbia River.

We have nuclear plants leaking radioactive tritium next to the Chattahoochee

and Altamaha Rivers, and radiation is detectible in the Savannah River

near Plant Vogtle.

How many radioactive solar panels or windmills have you heard of?

Annette Cary wrote for the Tri-City Herald yesterday,

Birds at Hanford vit plant spread contaminated waste,

Annette Cary wrote for the Tri-City Herald yesterday,

Birds at Hanford vit plant spread contaminated waste,

Work stopped Wednesday morning at parts of the Hanford vitrification plant after radioactive contamination was detected under a bird’s nest, according to Bechtel National.

The contamination is suspected of coming from mud used for the nest, which may have belonged to a swallow, said Bechtel spokesman Todd Nelson. Only a small amount of contaminated soil was found, and the contamination was at a low level.

Ralph Vartabedian wrote for the Los Angeles Times 14 August 2011, Safety doubts raised at U.S. nuclear waste cleanup project: Engineers and scientists say equipment being installed by Bechtel Corp. at the Hanford site in Washington state poses risks, but the Energy Department is letting work continue.

Senior scientists at the site said in emails obtained by The Times that Bechtel’s designs for tanks and mixing equipment are flawed, representing such a massive risk that work should be stopped on that part of the construction project.

Blaine Harden wrote for The Washington Post 29 February 2004, U.S. probes medical fraud at Hanford nuclear facility, about Steve Lewis, an electrician at Hanford,

His vapor exposure, which occurred in January 2002, flushed his face red and burned his lungs. Four months later, he had headaches, nosebleeds and was gagging on phlegm. He went to see Larry Smick, Hanford’s acting medical director, who diagnosed Lewis’s complaint as a pre-existing condition: “Allergic disease likely making him more sensitive to irritant vapors at work,” according to the doctor’s handwritten notes.

Lewis was incredulous. He had never had allergies. He said he tried repeatedly during the exam to get the doctor to talk about chemical exposure out at the tank farms, but Smick would only talk allergies.

“Quite honestly, that is when my bubble popped,” said Lewis, 51. “I could live with injury because these things do happen. I was not an angry employee up until they started trying to convince me that I hadn’t been injured.”

The diagnosis that infuriated the electrician is part of a years-long pattern of questionable medical and management practices at Hanford — first disclosed last fall by a nonprofit watchdog group called the Government Accountability Project — that is now triggering investigations by federal and Washington state officials.

And that wasn’t all, as Ralph Vartabedian wrote for the Los Angeles Times 7 March 2013, Firm in Hanford nuclear waste project settles fraud case: The contractor CH2M Hill agrees to pay $18.5 million in damages for time card fraud in the project in Washington.

More detail on the work in by Shannon Dininny for AP 1 June 2013, Storied nuke plant becomes environmental wasteland,

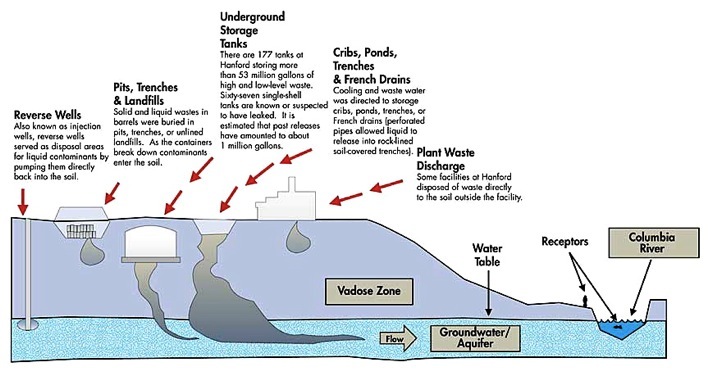

RICHLAND, Wash. (AP) — A stainless steel tank the size of a basketball court lies buried in the sandy soil of southeastern Washington state, an aging remnant of U.S. efforts to win World War II. The tank holds enough radioactive waste to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool. And it is leaking.

For 42 years, tank AY-102 has stored some of the deadliest material at one of the most environmentally contaminated places in the country: the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. This complex along the Columbia River holds a storied place in American history. It was here that workers produced the plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. on Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945 — effectively ending the second world war.

Today Hanford’s legacy is less about what was made here than the environmental mess left behind — and the federal government’s inability, for nearly a quarter-century now, to rid Hanford once and for all of its worst hazard: 56 million gallons of toxic waste cached in aging underground tanks.

Technical problems, mismanagement and repeated delays have plagued the interminable cleanup of the 586-square-mile site, prolonging an effort that has cost taxpayers $36 billion to date and is estimated will cost $115 billion more.

Add to that the leaks involving AY-102 and other tanks at the site, and watchdog groups, politicians and others are left wondering: Will Hanford ever really be free of its waste? If not, what will its environmental impact be on important waterways, towns and generations to come?

There’s more in the AP article, such as this:

In all, since that very first leak in the 1950s, at least 69 tanks are known to have excreted more than 1 million gallons of waste — and possibly far more — into the soil.

Not to worry:

The groundwater at Hanford already is contaminated, but scientists gauge the risks to be minimal because it would take decades for contaminants already in the soil to reach the Columbia River, the largest waterway in the Pacific Northwest. The closest tank sits 5 miles from the river, home to endangered fish and a source of drinking water for some 175,000 people immediately downstream.

So “minimal” means “your children and grandchildren will have a contaminated river”.

Plant Hatch,

chronically leaking radioactive tritium into groundwater,

and

same design as Fukushima,

is on the Altamaha River.

Plant Farley,

with

radioactive tritium in well water,

is just across the Chattahoochee River in Alabama.

Plant Vogtle,

with

direct radiation and airborne radiation on the river bank and on nearby roads,

is on the Savannah River,

which has detectible radioactivity in the river itself.

What about the

now-closed Crystal River nuke

in north Florida,

whose problem nobody wanted to pay to fix was

cracked containment concrete:

what will stop it from leaking?

All are above the Floridan aquifer, the source of our drinking water.

Once contamination gets into groundwater,

it doesn’t just vanish; it continues to spread.

Plant Hatch,

chronically leaking radioactive tritium into groundwater,

and

same design as Fukushima,

is on the Altamaha River.

Plant Farley,

with

radioactive tritium in well water,

is just across the Chattahoochee River in Alabama.

Plant Vogtle,

with

direct radiation and airborne radiation on the river bank and on nearby roads,

is on the Savannah River,

which has detectible radioactivity in the river itself.

What about the

now-closed Crystal River nuke

in north Florida,

whose problem nobody wanted to pay to fix was

cracked containment concrete:

what will stop it from leaking?

All are above the Floridan aquifer, the source of our drinking water.

Once contamination gets into groundwater,

it doesn’t just vanish; it continues to spread.

Have you ever heard of a leaking solar panel? How about a radioactive windmill?

-jsq

Short Link: